Oliver Burkeman Knows You Don’t Have Time

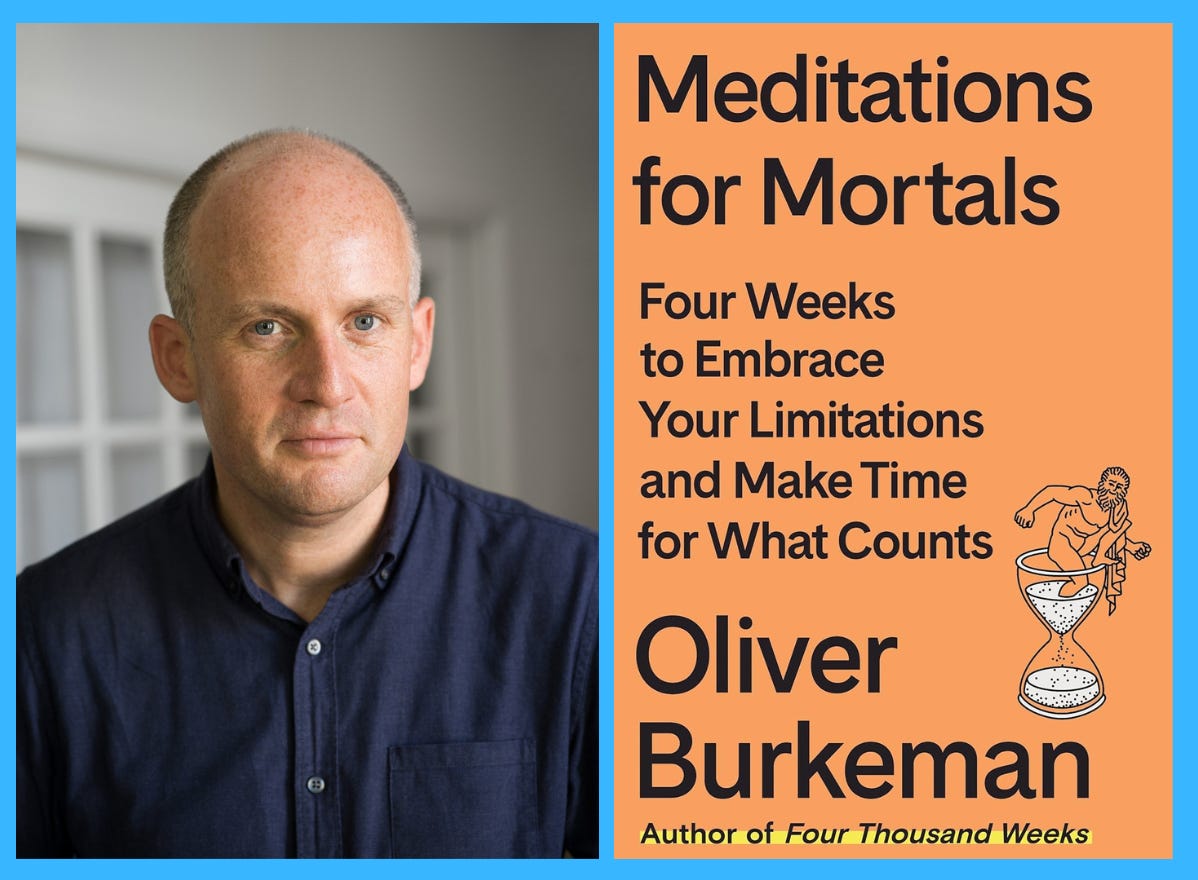

In 21 Questions, the bestselling author of Four Thousand Weeks and Meditations for Mortals reflects on printers, pacing, and why “being behind” is an illusion.

Oliver Burkeman is one of those rare thinkers who manage to mix urgency with generosity: urgency about how little time we have, generosity in how deeply he explores what matters most with it. A British journalist and author, Burkeman first made waves through his long-running column “This Column Will Change Your Life” in The Guardian. He is best known today for Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, a book that doesn’t tell you how to squeeze more in, but rather how to stop squeezing so tightly. His most recent book, Meditations for Mortals, is—in Oliver’s words—about “cultivating aliveness; staying sane and getting things done in a volatile and alarming world; and becoming more human in the face of technological threats to the human.”

That broader philosophy runs through all his work, and it’s what makes his perspective stand out in a crowded field of productivity gurus and lifehackers. He has a knack for treating life’s big constraints—death, failure, limitations—not as obstacles to positive thinking, but as portals to clarity. He educates in humility and intention and refuses the usual self-help fast food of “grind more, hustle harder.” He writes instead for people who want their lives back, or at least to stop pretending that time is something you can cheat. It’s no wonder that Oliver is among the rare authors to have had two books chosen as official Next Big Idea Club selections. I had the pleasure of interviewing him three years ago, and it turned into a conversation that still resonates with me today.

In this round of 21 Questions, Oliver’s responses capture exactly what makes his work so compelling: practical habits, hard-won wisdom, and a reminder that time is something to inhabit, not conquer.

—Panio

21 Questions with Oliver Burkeman

I couldn’t have written my last book without… three large whiteboards and a lot of sticky notes. Getting a structure in place is the milestone moment for me in writing a book, and with Meditations for Mortals this was a matter of moving concepts and stories and ideas around where I could see them, until clusters started to form.

What’s the thing most people get wrong about being a writer? I don’t know whether most people get this wrong, but there’s a general sense that nonfiction books are first researched (long hours in dusty libraries, days of interviews) and only then written up. That might be true for some kinds of writing, but for me these aren’t separate stages. Writing helps me narrow down what I need to research next, and it means that any given bit of research is always for some purpose, not vague and open-ended.

What’s something you wish you’d started doing five years ago? Nothing, I hope. I am so susceptible to getting stressed out by the feeling that I’m on the back foot—that I should have started doing X or Y or Z years ago—that I now try to be very mindful about not falling into that thought-pattern. I’m here. This is now. The rest is just fretting about things I can’t hope to control.

Hemingway wrote standing up; Edith Wharton, lying down. What are your quirks? I’m a fidgety writer—I write sitting down, but then get up every few minutes to pace around the room muttering to myself. It’s not a good trait in shared workspaces, but I believe it probably helps combat the negative effects of a sedentary lifestyle.

Do you read your reviews? Not every single customer review, perhaps, but published book reviews, certainly. And I am suspicious of people who claim otherwise, unless they’re so high-profile that there are too many to cope with.

Is there a book you wish you’d written? Basically any of Janet Malcolm’s. (If you haven’t read them you should!)

Have any tech tools made your job easier? This is retro, I know, but: a printer. Which is maybe surprising inasmuch as all printers are terrible, but a central part of my writing process is printing bits out and then typing them freshly back in. I find that this way, I make all sorts of edits and improvements effortlessly and almost unconsciously, with far better results than if I was fiddling around with sentences solely on screen.

What new tools or distribution channels do you want to try? I’m really interested in some of the ways I see people using YouTube recently for long-form exploration of ideas. I’m not sure why the platform seems relatively resistant to the hyper-stimulating and/or hyper-polarizing tendencies evident on TikTok and on (what I will always call) Twitter, but it does.

How has AI changed your writing process? Primarily by inspiring me to double down on the fundamentally human nature of the act of writing: to remember that the whole point of what I’m doing is that I’m a conscious, thinking, emoting sensibility, explaining how I see the world to other conscious, thinking, emoting sensibilities—or vice versa when I’m the reader. It’s not my current position that AI has zero role to play in that; for example, I use Perplexity.ai as a search engine. But I’m amazed when I see writers discuss using LLMs to handle large portions of the process of coming up with ideas or shaping them. For me as a reader, discovering that someone did that (or being able to tell, from the prose style) removes most of the interest I have in reading it.

Where do you find new ideas? I believe that what we call “finding” new ideas is mainly a matter of realizing that something you’d already been thinking about or discussing with other people is a viable idea for your writing. The difficult thing for me is not being interested in stuff, or noticing certain patterns in life, or grappling with certain problems, or talking with others about experiences they’ve had, or any of that. Rather, it’s noticing that one of these things is a perfectly good topic for a newsletter, or that it would be relevant to a book chapter I’m writing.

How do you keep track of new ideas? Following on from that, the important thing for me is to keep a disorganized freeform document in which I note any stray thought or idea or quotation or story that floats into my awareness, whether or not it seems like “a good idea” right now or not. Returning to that document, I’ll often find that one or more of those snippets jumps out: for some mysterious reason, it will feel full of life and ready to be written about.

What’s the best piece of professional advice you’ve ever received? That articles and newsletters and book chapters work best when you have one point to make, when you know what that point is, and when you explain that point pretty clearly, early in the piece. This doesn’t mean you can’t go down all sorts of rabbit-holes or make all sorts of additional sub-points. But you should figure out what that one main point is.

And the worst? I don’t recall getting any bad advice that I’ve actually taken and then regretted. There’s certainly been advice I rejected—to pursue a career in academia instead of journalism, for example—and I’m glad I rejected it, but then again, who knows what would have happened if I’d taken it? My life could have turned out immeasurably better or worse, or neither.

What is the one piece of advice you would give to recent graduates that want to make a living as a writer? It’s crushingly obvious, but the one thing that’s changed the most since I started out is the end of media gatekeepers, so that you really just are a writer in the very moment you click publish on something you’ve written. So the point is just to do it—start a newsletter, post mini-essays on social media platforms, anything. The beautiful asymmetry of writing online is that if people love something you’ve written, you can make a big splash with it, but if your early efforts turn out a bit boring or pointless, you won’t be publicly humiliated for it; instead, it’s just that nobody will notice.

Coffee, tea, or something stronger? Coffee. I mean, a gin and tonic or a beer too now and then, but definitely not while I’m writing or attempting to do anything remotely productive.

What's the most effective way you've found to build your email list? There are probably many things I should be doing, but my core strategy is just to make sure that the newsletters I send out are, to the best of my abilities, useful or helpful in a standalone way, ie., as opposed to just being sales pitches for my books or events. They’re also free, which isn’t very useful advice if a paid newsletter is part of your strategy, I know, but for me it’s more important for the list to be able to grow unobstructed by a subscription fee than it is to make money directly from the newsletter.

How many drafts before you show your editor? I barely think in terms of drafts, but when I think about my workflow for a piece or a subsection of a chapter, it starts with a brain-dump and free-writing; then I try to draw a diagram of the right structure, then I write a rough piece following that structure, then I write a neat version, and print it out and type it back in once more. So I suppose that’s four drafts.

Can you describe your ideal workday? I get up at 5ish, write or journal for an hour and a half of so before family breakfast/morning time and the journey to school, then I write for two to three hours more, then some other work, some exercise outdoors in the hills where we live, and an evening with family or friends or both. I mean I could add some other ideal elements like “at 2pm the mail arrives and includes an enormous check made out to me,” etcetera, but that’s the basic outline.

How does that compare to your actual workday? Sometimes it gets close! But ever since becoming a father I’ve had to learn to be more flexible, and while the process has sometimes been frustrating I am absolutely certain that becoming more flexible has made me a better writer, or at least one less prone to procrastination and indecision. An essential part of this for me has been finding ways to structure the day that don’t require the day to unfold exactly as I might have planned for it to unfold. So I might aim to do “at least 2.5 hours” on my main current project, for example, or to start by 10am latest—real goals, but ones that aren’t so brittle that they’ll shatter the moment something unexpected happens.

What do you wish you’d known when you were starting out? That nothing in the realm of writing or work is quite as high-stakes as people inclined to anxiety, like me, are liable to assume. You can produce a less-than-stellar article. You can mess up an interview. You can even miss a deadline, though you’re not supposed to say that. This isn’t a reason to slack off, or not to try to do your best, but it is definitely a reason not to let the challenges you’ll inevitably encounter freak you out too much.

Fill in the blank: In five years, successful authors will all be… the ones doubling down on their humanness. (I accept this may be wishful thinking.)

✨ Thanks to Oliver for joining us at Author Insider! You can learn more about his work at oliverburkeman.com and follow him on Substack here. While you’re at it, be sure to pick up a copy of his latest book, the national bestseller Meditations for Mortals.

✍️ Save Your Spot!

If today’s 21 Questions has left you hungry for more author wisdom, you’re in luck. Our upcoming Author Insider AMAs will feature Charles Duhigg, James Patterson, and Zibby Owens. Join us if you can, and keep building the kind of writing (and reading) life that feels fully alive.

Thursday, Sept 25, 12 p.m. ET — AMA with Charles Duhigg (paid members only)

Friday, Oct 3, 1 p.m. ET — AMA with James Patterson & Patrick Leddin (paid members only)

Thursday, Oct 9, 12 p.m. ET — AMA with Zibby Owens (free + paid subscribers)

👉 Sign up here if you haven’t already, and don’t miss the chance to join us live.

Hey! I love that book.