The Writer in the Woods

Trent Preszler on forests, patience, and the unexpected places ideas take root.

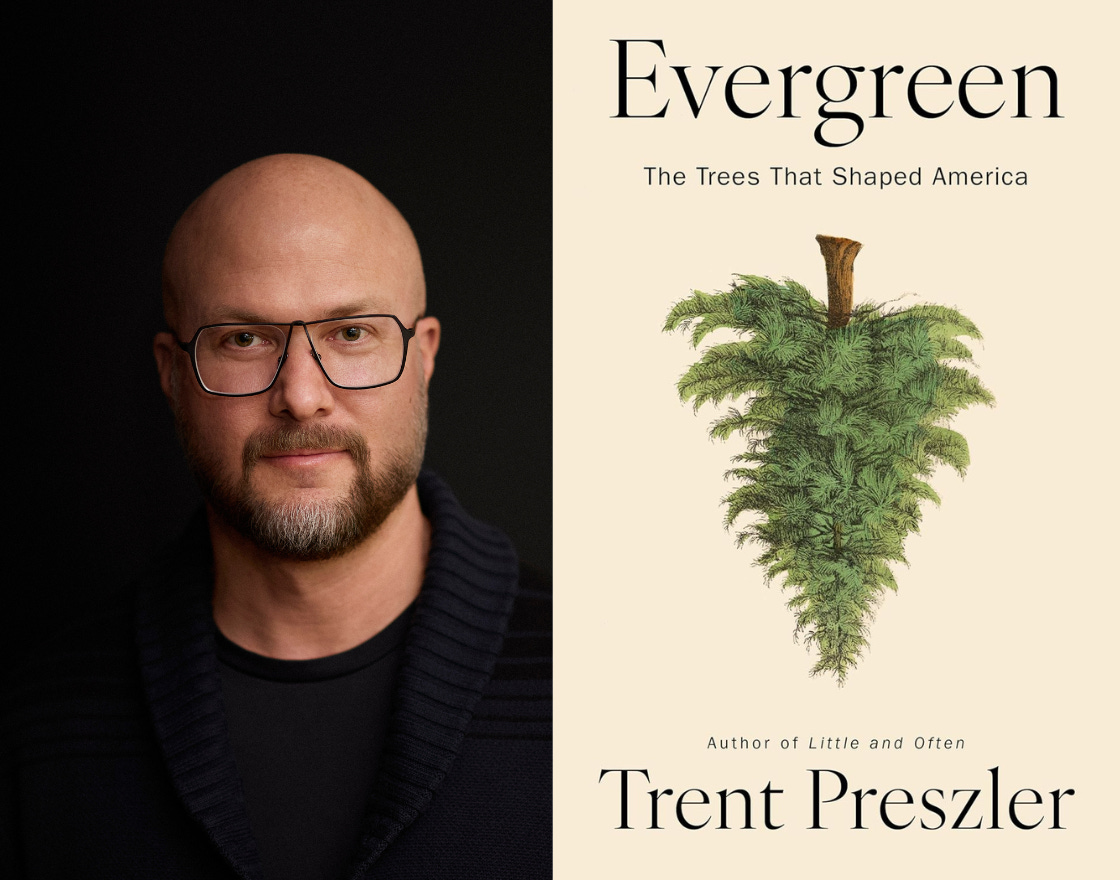

Trent Preszler’s life is straight out of a novel. He grew up on a cattle ranch in South Dakota, studied in a one-room schoolhouse, worked as an intern in the White House, made wine, built wooden boats, became a professor at Cornell and director of the Planetary Solutions Initiative, and in 2021, published a memoir, Little and Often, which became a USA Today best book of the year.

Whatever you do, don’t play “Never have I ever” with this guy.

His new book, Evergreen: The Trees That Shaped America, was just released this week. Deeply researched and beautifully written, Evergreen follows pines, firs, spruces, and sequoias across centuries of American history. Trent examines how the trees shaped (and were shaped by) culture, war, capitalism, traditions, and the collective imagination. More than a book about trees (although they deserve an entire library of books to be written about them), Evergreen is also about the small, quiet truths that nature offers us.

In this Author Insider Questionnaire, Trent talks about where ideas take root, why manual labor unlocks his creativity, and how a wooden canoe, a tea shop in Provincetown, and one perfectly timed Emmy ended up launching his writing career.

21 Questions with Trent Preszler

1. I couldn’t have written my last book without…

A willingness to disappear into forests for unhealthy stretches of time, plus a patient husband who tolerated the steady accumulation of pine cones, maps, and archival documents on our dining room table.

2. Hemingway wrote standing up; Edith Wharton, lying down. What are your quirks?

I write best after doing manual labor. I can be outside for six hours schlepping mulch in a wheelbarrow, weeding the gingko nursery, or pruning the Japanese maples, and then suddenly bolt inside in my mud boots to type like a man possessed. Something about working with dirt unlocks my brain synapses. I might sit there locked in a fever dream of inspiration for hours or days, bribing myself to keep going with promises of Laffy Taffy and Chardonnay.

3. Do you read your reviews?

A very wise man (my agent) once advised me not to, based on the theory that human brains are Velcro for criticism and Teflon for praise. When I cave and look anyway, it feels like sharpening a chainsaw: equal parts curiosity and dread. You hope it might make things cleaner; you also know you could lose a finger in the process. (Fortunately, I still have all 10 fingers.)

4. Kiss, marry, kill: podcasts, newsletters, and speaking gigs.

Kiss podcasts (intimate, fun, and nobody expects you to wear pants)

Marry speaking gigs (steady, loyal, occasionally glamorous)

Kill newsletters (they multiply like invasive weeds)

5. Is there a book you wish you’d written?

The Overstory by Richard Powers, for its audacity and utter genius.

6. Have any tech tools made your job easier?

Noise-canceling headphones and the voice memo app on my phone. Almost everything else is a fragile truce between me and Silicon Valley. I only recently learned how to operate the Apple TV remote, and even that feels provisional.

7. How has AI changed your writing process?

AI hasn’t changed my writing and is a shockingly terrible ghostwriter (thank God). The voice still has to be mine and every sentence still has to earn its way through my fingers onto the page. But it has changed everything around the writing process. AI is a decent low-level research assistant that can help me plow through volumes of historical data that could otherwise take months to read.

At Cornell, I teach more than 200 undergraduates who drag AI into the classroom like an extra appendage. They’re currently in the honeymoon phase of AI, where they enjoy generating answers to life’s greatest questions in seconds, but they struggle mightily when asked to separate their own thoughts from what a robot hands them. I want them to understand where an answer comes from and how to interrogate it, but AI is robbing them of those skills before they ever had a chance to develop. That’s the part that keeps me up at night.

8. Where do you find new ideas?

Pine forests, the nails-and-screws aisle of hardware stores, and conversations that happen on long car rides when nobody is looking at their phone.

9. How do you keep track of new ideas?

Thousands of Post-Its, tiny notebooks, the backs of NYSEG bill envelopes, and voice memos recorded while walking in the woods. My phone is a graveyard of mumbled tree facts.

10. What’s the best piece of professional advice you’ve ever received?

“Teach what you love.” Dean Zhao told me that the day he hired me at Cornell. It sounds simple and a little bumper-sticker-y, but if you’re going to talk to lecture halls full of teenagers for a living, it had better be about something that lights you up on the inside.

11. What is the one piece of advice you’d give to recent graduates who want to make a living as writers?

First, can we be honest? Very few people make a living on writing alone. Almost every published author I know has a day job. Most are professors at universities which provide us with the incredible luxury of being paid to think and write. Some are entertainers, influencers, podcasters, and serial side-hustlers. But the kind of book deal that allows you to pay the mortgage and the property taxes and the health insurance premium and the kid’s tuition is exceedingly rare.

But you asked me to give recent graduates a piece of advice, so here you go: Write the book you think the world cannot live without.

13. What’s on your nightstand right now?

Raw Dog: The Naked Truth About Hot Dogs by Jamie Loftus. Side-splittingly funny and weird in the best way. I love deep-dive nonfiction (surprise!), so I also have a stack of unread books about fire, fungus, capitalism—plus a novel to keep me honest.

14. Foreign rights, audio rights, film rights: which have been the most valuable to you?

Audio. Both my books live differently when spoken aloud. I guess trees and grief and history suit the human voice. Plus, aren’t trees the original storytellers?

14. How did you find your agent?

By complete accident or fate, depending on how mystical you’re feeling. In 2018, a local Long Island beat reporter made a short documentary about my stumbling, bumbling attempt to build a wooden canoe using my late father’s beat-up tools. She won a New York Emmy for it, and suddenly my public profile started behaving like it had stuck its finger in a light socket. Fast-forward a bit: a literary agent named Adam Chromy walks into a tea shop in Provincetown, MA with his wife Jamie Brenner (a fantastic novelist). They’re chatting with the owner about characters for her next book, including a boatbuilder. The owner says you should check out this canoe builder on Instagram. Adam does, then emails me out of the blue, something like “I saw your story. Let me help you turn it into a book.” And that was that. One canoe, one Emmy, one tea shop, one agent, and two books later, here we are.

15. What’s the best non-writing skill that’s helped your writing career?

Boatbuilding taught me patience, precision, and the understanding that shaving off too much at once (wood or words) is a tough thing to undo.

16. Coffee, tea, or something stronger?

Coffee in the morning. Tequila, lime, rocks, salt at night.

17. What’s one marketing tip you’d give a new author?

Remember that marketing is just a fancy word for connecting. I know this opinion may ruffle feathers in the Meta-verse, but I genuinely believe that one conversation with a bookstore owner who loves your work is worth more than 10,000 drive-by impressions on a social media feed. I simply don’t buy the popular narrative that a person who watches a seven-second clickbait video suggested to them by the algorithm is also a person who will buy your book. The readers who matter most are the ones who linger, ask questions, and decide they want your whole messy 250-page story in their life, not just seven seconds of it.

18. How many drafts before you show your editor?

Tough call, maybe three? The first draft is utter nonsense. Chaos. The second is a raging, out-of-control forest fire. The third is something that resembles a hiking trail through dense woods. Only then do I invite my agent or editor in with a compass and a strong beverage.

19. What do you wish you’d known when you were starting out?

That writing is stubbornly lonesome work. For years, your book lives in a hermetically sealed bubble with just you, your many insecurities, and an editor who may or may not occasionally remind you to breathe. Then one day, after all that secrecy and solitude, the book steps into the full glare of public fascination. That transition from absolute privacy to everyone suddenly having an opinion about it is terrifying and brings me more anxiety than I care to admit (though I suppose I just did).

20. Fill in the blank: In five years, successful authors will all be _____

Unmistakably original, because AI can only imitate what already exists.

21. What is your new book about?

Evergreen is basically the courtroom drama trees would deliver if they were called to the witness stand and sworn in. Pines, firs, spruces, and sequoias have kept their receipts on war, capitalism, colonialism, suburbia, joy, disaster, Christmas, the whole shebang. I just wrote down what they’ve been trying to tell us for 386 million years.

Want More Insights?

If you enjoyed this questionnaire, you’ll love the rest of Author Insider—real talk, publishing insights, and creative wisdom from bestselling authors and industry pros.

Subscribe free (or paid, if you’d like to support our work) and join the community.

Until next time,

Panio Gianopoulos

Editorial Director, Author Insider & The Next Big Idea Club